BY: DAVID PATON,1, NADINE GIBBS1 and PHIL CLAPHAM2

1Southern Cross University Whale Research Centre, PO Box 157 Lismore, NSW 2480, Australia

2Northeast Fisheries Science Center, 166 Water Street, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA

INTRODUCTION

On 11th March 2003, the Fijian Government approved the declaration of Fiji’s Exclusive Economic Zone as a Whale Sanctuary. This declaration is in keeping with the Fijian government’s international obligations under the Convention on Biodiversity and the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS). The declaration also acts as a catalyst for research and raising public understanding and ability to manage Fiji’s marine biodiversity.

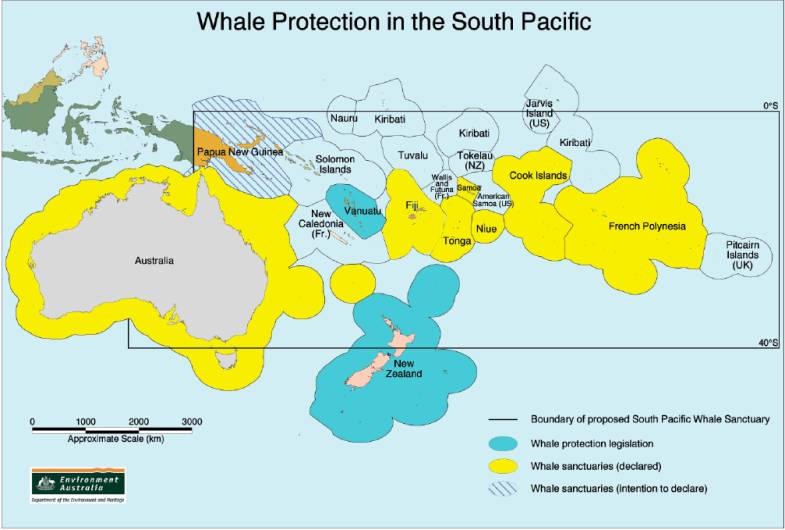

This declaration complements the existing South Pacific whale sanctuaries declared in the Cook Islands, French Polynesia, Niue, and Australia. In addition to these sanctuaries, New Zealand and Vanuatu have legislation in place that protects whales within their territorial waters. Whales in the Kingdom of Tonga are protected by a Royal decree from the King. Figure 1 indicated the current status of whale protection in the South Pacific.

This paper presents a brief description of the Fijian Whale Sanctuary and an overview of historical and current knowledge of cetacean species known or believed to inhabit the region.

Boundaries and area

The Fiji islands are located in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, south of the equator and north of the Tropic of Capricorn. Fiji’s EEZ covers an area of 1.26 million sq km. Together, the Fijian islands make up an archipelago of over 300 islands, with the combined land mass that occupies less than 1.5% of the total area. The islands lie between latitudes 120 and 210 South and between longitudes 1770 East and 1750 West. Islands within the region vary in size from very small patches of land a few metres in diameter, to Viti Levu (‘big island’), with an area of 10, 390 km2. Only about one-third of the islands are inhabited, mainly due to isolation or lack of fresh water.

Cetacean species in the sanctuary

The current status of many species of cetaceans in the waters of Fiji is largely unknown. Much of the available information on the occurrence of cetaceans in Fijian waters comes from whaling data and anecdotal information (Reeves et al 1999; Paton & Gibbs 2002). However, recent investigation of unpublished records of the late Dr William Dawbin, indicate that a land-based sighting survey had been undertaken in Fiji during the austral winters of 1956, 1957 and 1958. In association with the land-based surveys, Discovery tagging of whales was undertaken. A preliminary analysis of these data was undertaken last year by Paton & Clapham (2002), and Dawbin’s data substantially add to the knowledge of the historical abundance and distribution of cetaceans in the region.

In addition to these unpublished data, records of recent sightings of cetaceans in the Fiji area are kept by Nai’a Cruisers base in Fiji. Reeves et al (1999) and Paton & Gibbs (2002) have undertaken reviews of cetacean sightings within the region of the South Pacific which includes Fiji. These reviews, in conjunction with a preliminary survey conducted in the Lomaiviti Group of Fiji by Paton and Gibbs during 2002, are the only documented recent assessments of the status of cetaceans within Fijian waters.

The current status of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the waters of Fiji is largely unknown. Some humpbacks were apparently taken by Yankees or other whalers during the 19th century (Townsend, 1935), although the sparse existing data suggest that such catches were infrequent and opportunistic in nature. There were no known catches of humpbacks in this region during the 20th century, and as a result there is no published information on the relative abundance of this species in Fiji during the peak period of Southern Hemisphere humpback whaling.

Preliminary examinations of data from Dawbin’s surveys conducted from 1956 to 1958 indicate that humpback whales were considerably more abundant around Fiji in the late 1950’s than they are today (Paton & Clapham, 2002). Figure 2 indicates the weekly counts of humpbacks for the three years in which the surveys were conducted. Low numbers of whales were observed in May, rising to a peak between late July and late August and then declining again to very low levels in early October. Substantially more humpbacks were recorded in 1957 than in the other two years, with a maximum weekly count of almost 238 humpbacks recorded in the week beginning 21 August. There are a number of limitations regarding the weekly summaries given by Dawbin in his data, which relate to details of sighting effort. However, the data are important because they represent the only scientific information on the occurrence of humpbacks in this region.

During the period of Dawbin’s surveys (1956-58) a total of 142 humpbacks were marked with Discovery tags. Two of these animals tagged by Dawbin in Fijian waters were recaptured in New Zealand – one at Cook Strait and one at Great Barrier Island – on dates which showed that they were moving northward when traveling along the east coast of New Zealand. It can therefore be assumed that a portion of the population that migrated to Fiji traveled through New Zealand waters. In addition, a third animal which was tagged in Fiji was recaptured near Moreton Island on a date which indicated that it was almost certainly southbound along part of the coast of eastern Australia (Dawbin, 1964). The Soviets also recovered three Discovery tags originating from Fiji, one off eastern Australia and two others in the high-latitude portions of eastern Area V and western Area VI in the Antarctic (Mikhalev, 2000).

Paton and Gibbs undertook a preliminary assessment of the current abundance of humpbacks in the Lomaiviti Island Group (the area previously surveyed by Dawbin) in 2002. This survey confirmed the current presence of humpback whales in the region, however well below the numbers recorded by Dawbin in the 1950’s. It also confirmed the importance of Fijian waters as part of the breeding grounds for humpback whales with anecdotal reports of the presence of young calves and the first documented recording of humpback song, suggesting the occurrence of courtship and mating behaviours within Fijian waters.

A scarcity of whales in Fiji today would imply that this population remains severely depleted and has yet to recover from commercial whaling, a situation which appears to be the case among humpback whales in other parts of Oceania (Garrigue et al., 2000). Lack of recovery is likely due to the probable catch history of this stock. During the period covered by Dawbin’s surveys, humpback whales were being taken from their high-latitude feeding grounds in the Antarctic. Furthermore, the survey period ended just before two years of very large illegal catches by the Soviet Union. In the 1959/60 Antarctic whaling season, Soviet whalers killed almost 13,000 humpback whales in the high-latitude portions of Area V and Area VI (Mikhalev, 2000). Although the origin of the humpbacks that Dawbin observed in Fiji is unknown, it is likely that they were part of one of these two populations. The 1959/60 Soviet catches were immediately followed by the effective collapse of shore whaling for humpbacks in New Zealand. An additional 12,000 humpbacks were killed by the USSR in the following year (1960/61), and while the exact locations of these catches are not known they were primarily taken in Areas IV and V (Mikhalev, pers. comm.).

While Reeves et al. (1999) report the Bryde’s whale (Balaenoptera edeni) to be the most common mysticete in the Oceania region, there have only been two anecdotal sightings of this species in Fijian waters (R. Barrel pers. comm.). Bryde’s whales, unlike most other mysticetes, are known to inhabit the Oceania region on a year-round basis. Although data are scarce, these animals would probably belong to the western South Pacific stock (130 E – 150 W) (IWC 1982, in Reeves et al., 1999). The exploitation of Bryde’s whales in the Oceania region has been very limited, consisting primarily of catches by Japanese whalers under special scientific permits during the late 1970’s. Most of the information on distribution and relative abundance comes from Japanese catch, tagging and sighting data obtained during the late 1970’s and early 1980’s. In 1976, between October and November, a Japanese whaling expedition caught Bryde’s whales in a region between New Zealand and Fiji. Bryde’s whales were also observed during the same expedition between New Caledonia and Fiji (Ohsumi, 1978). The stomachs of captured Bryde’s whales were sampled and it was found that they contained exclusively euphausiids (Kawamura, 1977). In late October and early November of 1977, Japanese whalers observed, marked and killed Bryde’s whales in a large area between the Tuamotu Archipelago and Fiji.

Sei whales (Balaenoptera borealis) are reported to have a worldwide distribution but are found mainly in cold temperate to subpolar latitudes rather than the tropics or near the south and north poles (Horwood, 1987). Although Reeves et al. (1999) have no records for sei whales in the Oceania region, Dawbin’s records indicate that sei whales were observed periodically in Fijian waters in the late 1950’s. Dawbin reports tagging seven sei whales during the three years of surveys in Fiji. It is assumed that there would have been a number of other sei whales observed from the three land stations that were not tagged. Had these animals only been observed from the land stations, it might have been possible to confuse these animals with Bryde’s whales as there is frequent failure to distinguish sei from Bryde’s (Mead, 1977; Rice, 1979; Horwood, 1987; Shimada & Pastene, 1995). However verification of the species can be confirmed by Dawbin’s close approach during the tagging operation (Dawbin, 1959; Dawbin unpublished data). Supporting this observation is a report by Ohsumi (1979) of a sei whale sighted south of New Caledonia in November 1977. No data are available on recovery of tags from sei whales.

Fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) are more cosmopolitan in their distribution and more predictable in their seasonal movements than sei whales. Although it is generally believed that at least some fin whales make pole-ward feeding migrations in summer and move towards the equator in winter, few actual observations of fin whales in tropical and subtropical waters have been documented (Mackintosh, 1942). Two anecdotal reports of fin whales off the south coast of Viti Levu (Ed Lovell pers. comm.) are supported by two documented sightings of fin whales south of Fiji during October and November of 1997 (Ohsumi, 1979).

Minke whales (probably Balaenoptera bonaerensis but possibly also B. acutorostrata sp.) have been reported in Fijian waters from Japanese sighting surveys between 1976 and 1987 (Kasamatsu et al., 1995) and anecdotal observations (R. Barrell pers. comm.). These observations are further supported by documented sightings of minke whales south of Fiji in October 1977 (Ohsumi, 1979).

Sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) were extensively taken in Fijian waters during the 19th century (Townsend, 1935). Paton and Gibbs reported that although sperm whales have been sighted in all seasons of the year, the bulk of the records are for the winter and spring seasons.

During Dawbin’s survey in the austral winter and spring seasons between 1956 and 1958 around Ovalau, Wakaya and Naigani, a total of 20 sperm whales were marked with Discovery tags. It is assumed that additional sperm whales were sighted but were not tagged during this period. No information is available on any recoveries of these Discovery tags. This indicates that historically, sperm whales occurred in significant numbers in the Fijian area. Recent anecdotal sightings and stranding events indicate that sperm whales still frequent the area, however they are possibly well below the original abundance as a result of whaling in the 18th and 19th centuries.

A number of smaller odontocetes have also been recorded in the waters of Fiji. These include false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) and short-finned pilot whales (Globicephala macrorhynchus). It is presumed that these species are widespread and common throughout the region (Reeves et al., 1999). These species are suspected of taking fish from long-line fishing operations throughout the region. Dawbin (1959) reports that he tagged three blackfish during his tagging operations in Fijian waters. Blackfish is the term often used to refer to a range of smaller odontocetes, which include false killer whales and (most commonly) pilot whales, among others.

Spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris) are the most commonly seen cetacean species and, based on anecdotal information, appear to be present year round with a widespread distribution in Fijian waters. Spinner dolphins were observed by Paton & Gibbs during the surveys conducted in the Lomaiviti Island Group during 2002. A dolphin-watching operation is currently focusing on observing spinner dolphins on the western side of Viti Levu. In addition, killer whales (Orcinus orca), Fraser’s dolphin (Lagenodelphis hosei) and the rough-toothed dolphin (Steno bredanensis) have all been recorded in Fijian waters.

Additional species potentially found in Fijian waters

Various authors have noted that blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus, as well as B. m. brevicauda), which occur during summer in high latitudes, move into the subtropics and tropics in winter (Harmer, 1931; Mackintosh, 1942, 1966; Wheeler, 1946; Yochem & Leatherwood, 1985). Non-migratory populations may also be present in certain highly productive low-latitude areas. Reeves et al. (1999) report that elsewhere in the central and western tropical Pacific, evidence of blue whales is almost entirely lacking except near the Solomon Islands. However Ohsumi (1979) reported a sighting of two blue whales in November 1977, west of Tonga. It is therefore possible that blue or pygmy blue whales may be rare visitors to the Fiji region.

Odontocetes that have not been noted in Fijian waters but which are considered reasonably common and widespread throughout the western and central tropical South Pacific include the Pantropical spotted dolphin (Stenella attenuata), melon-headed whale (Peponocephala electra), Risso’s dolphin (Grampus griseusi), striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba) and Cuvier’s beaked whale (Ziphius cavirostris).

Whaling History

There is documented evidence of whaling activities in the Fijian region from the 19th Century, with activity being primarily based on sperm whales (Townsend 1935); however it is believed that humpbacks may have also been taken in small numbers. There is no evidence of recent whaling activities within Fijian waters.

Even though Dawbin’s data indicate that humpbacks, among other species, were once relatively plentiful in the Fijian region, there is no documented evidence of shore-based whaling by native Fijians.

Fisheries Interactions

Fishing companies in Fiji, like many parts of the South Pacific, have growing concerns in relation to interactions between cetaceans and the long-line industry (G. Southwick, pers. comm.). These concerns stem from the removal of hooked fish from pelagic longlines by small toothed whales (believed mainly to be short-finned pilot whales and/or false killer whales).

This issue was highlighted by a recent meeting involving Government authorities, industry representatives and researchers from throughout the South Pacific, held in Samoa in November 2002.

The workshop reviewed the subject in detail, and potential means of resolving these conflicts. A report from this workshop, including an Action Plan and a list of possible mitigation measures, is being developed and will be provided to SPREP member governments for their endorsement. In addition to this report, an Executive Summary of the Report and a proposed Action Plan are currently being developed for review by the Marine Sector Working Group, and relevant inter-governmental organisations (including SPREP, FFA, SPC and Pacific Islands Forum) (Donoghue 2002).

Whale watching

At least one operator is currently conducting dolphin-watching activities off the west coast of Viti Levu; this activity is based primarily on spinner dolphins. Other cetacean watching is opportunistic in nature as part of fishing/diving and other tourist-based activities.

Cultural Issues

Sperm whale teeth form a very important part of Fijian culture. It is believed that the use of these teeth as ransom or “barter money” was introduced to Fiji from Tonga during the late 18th century (Derrick, 1950). The teeth of sperm whales became so important in Fijian culture as an item of chiefly exchange and central to expressions of kinship that they eventually came to define the essence of tabua, “the price of life and death, the indispensable adjunct to proposals (whether of marriage, alliance, or intrigue), requests and apologies, appeal to the gods, sympathy with the bereaved” (Derrick, 1964). Lever (1964) indicated that the importance of polished sperm whale teeth in Fijian culture continued at least until the 1960’s. Reports from recent stranding events in Fiji indicate that in many cases the jaws and teeth of sperm whales are regularly removed from animals before authorities arrive at the stranding location. According to IWC (1994), the Fijian trade in sperm whale teeth “did not relate to a local fishery”. The agenda of a meeting held in Fiji in relation to establishing a whale sanctuary in Fijian waters (March 2002), included an item on tabua and accessing teeth from international sources. This demonstrates that sperm whale teeth still have a major role within Fijian culture.

Cetacean Research in the Fijian Islands Whale Sanctuary

Current cetacean research in the Fijian Islands Whale Sanctuary is focused on undertaking surveys which allow a comparison of the current status of humpback whale numbers in relation to the results obtained during Dawbin’s surveys of the 1950’s. By replicating, where possible, the methodology used by Dawbin in conducting the land based surveys conducted 44 years earlier, a comparison with historical data is possible.

Complementing this methodology, where conditions are suitable and permits granted by the relevant authorities, photo-identification is also undertaken. Identification photographs are compared against the South Pacific humpback whale catalogues managed by the South Pacific Whale Research Consortium. Acoustic monitoring is also undertaken. It is also proposed, pending permits being granted by the Fijian Government, to collect genetic samples during the 2003 survey.

These data will assist in:

i. determining the local abundance of humpbacks in the Fijian region,

ii. documenting habitat use and behaviour of whales in the Fijian Islands,

iii. assessing the degree of exchange between the Fijian Islands and other areas of the South Pacific using photo-identification, and

iv. through the collection of genetic samples from Fiji, contributing to an ocean-wide investigation of the genetic structure of South Pacific humpback whales.

Protective measures

Following the declaration of the Fijian Islands Whale Sanctuary, the Fijian government has drafted a Marine Management Bill that, when endorsed by the Cabinet and enacted by Parliament, will protect marine mammals within Fiji’s EEZ.

Protection of marine mammals within Fijian waters complements the rapidly expanding area of whale sanctuaries throughout the South Pacific. This is significant as this region represents the breeding grounds for many great whale populations, which now have the potential to recover from the impacts of the overexploitation to which they were subjected.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the great contribution of the late Bill Dawbin to the study of humpback whales throughout the South Pacific. The authors would also like to acknowledge the assistance of the International Fund for Wildlife (IFAW) and Environment Australia who funded the research undertaken in Fiji by DP and NG, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) South Pacific Office in Fiji, for supplying up to date information on the Fijian Whale Sanctuary. We would also like to acknowledge those persons, particularly Rob Barrell and Cat Holloway from Nai’a Cruisers, who contributed cetacean sightings from the Fiji region and Manasa Sovaki (Department of Environment) for his assistance in coordinating cetacean surveys in Fijian waters. Figure 1 was kindly supplied by Environment Australia.

REFERENCES

Dawbin W. H. 1956. Whale marking in the South Pacific waters. Norsk Hvalfanst-Tidende 4: 485-508.

Dawbin W.H. 1959. New Zealand and South Pacific Whale marking and recoveries to the end of 1958. The Norwegain Whaling Gazette 5: 214-238.

Dawbin W. H. 1964. Movements of humpback whales marked in the southwest Pacific Ocean 1952 to 1962. Norsk Hvalfanst-Tidende 3: 68-78.

Derrick, R.A. 1950. A History of Fiji, Volume 1. Government Press, Suva, Fiji. 250pp. Cited from Reeves et al. 1999.

Derrick, R.A. 1964. Cited from Reeves et al. 1999. Marine Mammals in the area served by the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP). SPREP Apia.

Donoghue 2002 Cetacean Interactions with Commercial Longline Fisheries in the South Pacific Region: Approaches to Mitigation. Workshop proposal.

Garrigue, C., Aguayo, A., Baker, C.S., Caballero, S., Clapham, P., Constantine, R., Denkinger, J., Donoghue, M., Flórez-González, L., Greaves, J., Hauser, N., Olavarría, C., Pairoa, C., Peckham, H. and Poole, M. 2000. Movements of humpback whales in Oceania, South Pacific. Unpublished paper presented to the International Whaling Commission: SC/52/IA6.

Harmer, S.F. 1931. Southern whaling. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London, Session 142, 1929-1930: 85-163. Cited from Reeves et al. 1999.

Horwood, J. 1987. The Sei Whale: Population Biology, Ecology and Management. Croom Helm, London. 375pp. Cited from Reeves et al. 1999.

IWC. 1982. Report of the Scientific Committee. Report of the International Whaling Commission 32: 43-149.

IWC. 1994. Report of the workshop on mortality of cetaceans in passive fishing nets and traps. Report of the International Whaling commission (Special Issue) 15: 6-71.

Kawamura, A. 1977. On the food of Bryde’s whales caught in the South Pacific and Indian oceans. Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute (Tokyo) 29: 49-58. Cited from Reeves et al. 1999.

Kasamatsu, F., Nishiwaki, S. and Ishikawa, H. 1995. Breeding areas and southbound migrations of southern minke whales Balaenoptera acutorostrata. Marine Ecology Progress Series 119: 1-10.

Lever R.J. 1964. Whales and whaling in the western Pacific. South Pacific Bulletin 14(2), 33-36. Cited from Reeves et al. 1999.

Macintosh, N.A. 1942. The southern stocks of whalebone whales. Discovery Reports 22: 197-300. Cited from Reeves et al. 1999.

Mead, J.G. 1977. Records of Sei and Bryde’s whales from the Atlantic coast of the United States, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean. Report of the International Whaling Commission (Special Issue) 1: 113-116. Cited from Reeves et al. 1999.

Mikhalev, Y. 2000. Biological characteristics of humpbacks taken in Area V by the whaling fleets Slava and Sovietskaya Ukraina. Unpublished paper presented to the International Whaling Commission: SC/52/IA11.

Ohsumi, S 1978. Provisional report on the Bryde’s whales caught under special permit in the Southern Hemisphere. Report of the International Whaling Commission 28: 281-287.

Ohsumi, S. 1979. Provisional Report of the Bryde’s whales caught under special permit in the Southern Hemisphere in 1977/78 and a Research Programme for 1978/79. Report of the International Whaling Commission 29: 267-273.

Paton. D. & Gibbs N. 2002 Documented and Anecdotal Cetacean Sightings, 1761 – 2001, in the Samoa, Fiji, Vanuatu and Solomon Island Regions Report to Environment Australia.

Paton D. and Clapham P. 2002. Preliminary analysis of humpback whale sighting survey data collected in Fiji, 1956 – 1958. IWC Scientific Committee : SC/54/H7.

Reeves, R., Leatherwood, S., Stone, G., and Eldredge, L. 1999. Marine Mammals in the area served by the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP). SPREP Apia.

Rice, D. W. 1979. Bryde’s whales in the equatoral eastern Pacific. Report of the International Whaling Commission 29: 321-324.

Townsend, C.H. 1935. The distribution of certain whales as shown by logbook records of American whaleships. Zoologica 19: 1-50 + 6 maps.